Citizen Villain and Citizen Thrill

The not so rosy picture for technology, society, and government

Recently I wrote about Citizenville - Gavin Newsom’s optimistic case for technology reshaping government, the provision of government services, and how citizens interact with the institutions that serve them. The book reads like a love letter to government-techno-utopianism, which I find quite compelling, if overly optimistic.1

There are a number of less rosy pictures of the influence of technology on government and society. Ranging from slightly negative to downright dystopian, these accounts can wipe the shiny appeal off of Newsom’s account. Negativity itself isn’t instructive, but it is important to recognize alternate lenses through which to view the world when thinking about the interplay of technology, government and society.

Over the course of a couple of posts, I will discuss these worldviews and then discuss them alongside Citizenville.

Citizen Villian - What’s to come

A preview of five pessimistic narratives of the interplay of technology, government, and society [See below]

An explanation of each narrative in great depth

A brief comparison of these arguments to Citizenville

A look at what’s next, where this could all go, and how we avoid the pitfalls of these narratives when thinking about governing moving forward.

Citizen Villain: 5 distinctly negative counternarratives to Citizenville

There are many more than just five narratives on how technology negatively impacts government, the ability to govern, and civic life. So, at the outset, I want to make clear that these five are not exhaustive. They are illustrative. Illustrative of various patterns that I find compelling and powerful for their explanatory power beyond the obvious tropes of “progress good, slow government bad,” which seem to permeate so much of the noise in critiquing how government operates.

I categorize these narratives as follows:

Citizen Thrill - Technological distraction driving commercialism and distraction at the expense of learning, critical thinking, and civic engagement.

Citizen Disassemble - Technology eroding the power of traditional institutions of authority (government, media, etc.) without building viable alternatives.

Citizen Stand Still - Government falling too far behind technological progress to no longer be relevant as a regulatory body.

Citizen Dollar Bill - Corporate entities filling the void created by government and/or replacing government as the main organizing entities in society, providing more public services, and cementing the transition from citizen to consumer.

Citizen Ant Hill - Humanity suffering (or ceasing to exist) due to misaligned artificial intelligence.

Admittedly, getting these all to (sort of) rhyme with Citizenville is a bit corny. But since ~20 people will read this post, there won’t be too many eyerolls. The rest of this post will look at the first narrative, leaving the others for future work.

Citizen Thrill - Idiocracy’s warning

The first narrative is well worn at this point and speaks to the broader impact of technology on society, not just civic engagement. This argument is less about government’s use of technology and more about societal change.

The narrative is best captured by Idiocracy, a satirical science fiction movie released in 2006, depicting the impacts of declining collective intelligence over time. The plot follows the protagonist, Joe Bauers (Luke Wilson), a completely average man, and Rita (Maya Rudolph), a sex worker, who are cryogenically frozen by the U.S. military in an experiment, only to be forgotten about and wake up 500 years in the future.

Upon waking, Joe and Rita find that intelligence and critical thinking have significantly deteriorated throughout society, leading to a world dominated by anti-intellectualism, commercialism, and cultural decline. Through a series of funny (in a middle school boy humor sort of way) exchanges, Joe discovers he is no longer average. He is now the smartest man on Earth. Navigating a world in which an energy drink replaced water as the primary thirst-quencher, “Ow! My balls!” is the most popular show on television, mountains of trash riddle the landscape, and crops no longer grow, Joe and Rita must try to save society from the brink of collapse.

Admittedly, the movie was not a smashing success when Fox tepidly released it over 15 years ago.2 But it did gain somewhat of a cult following for the chord it struck for its morons-inherit-the-earth messaging. There are many versions of the “Idiocracy is coming true” narrative, especially following the election of President Trump (in the movie, Terry Crews stars as President Camacho, a gun-wielding, juiced up entertainer who uses loud, patriotic calls to rally his base - quite similar to Trump). And it is scary to recognize the parallels - the ubiquitous corporate branding of everyday life, the never-ending distraction of screens and entertainment, the rising populist demagoguery, the derision of experts, and the looming climate crisis.

Idiocracy is a movie that warns of societal decline. And much of this decline manifests through individuals interacting with technology as a distraction mechanism, focused on short-term pleasure. And while it can feel like a slightly more dystopian version of grandparents shaking their heads and saying “kids these day,” the evidence is everywhere at this point, so just a quick summary of some themes to illustrate the prophetic nature of the movie and why it has staying power:

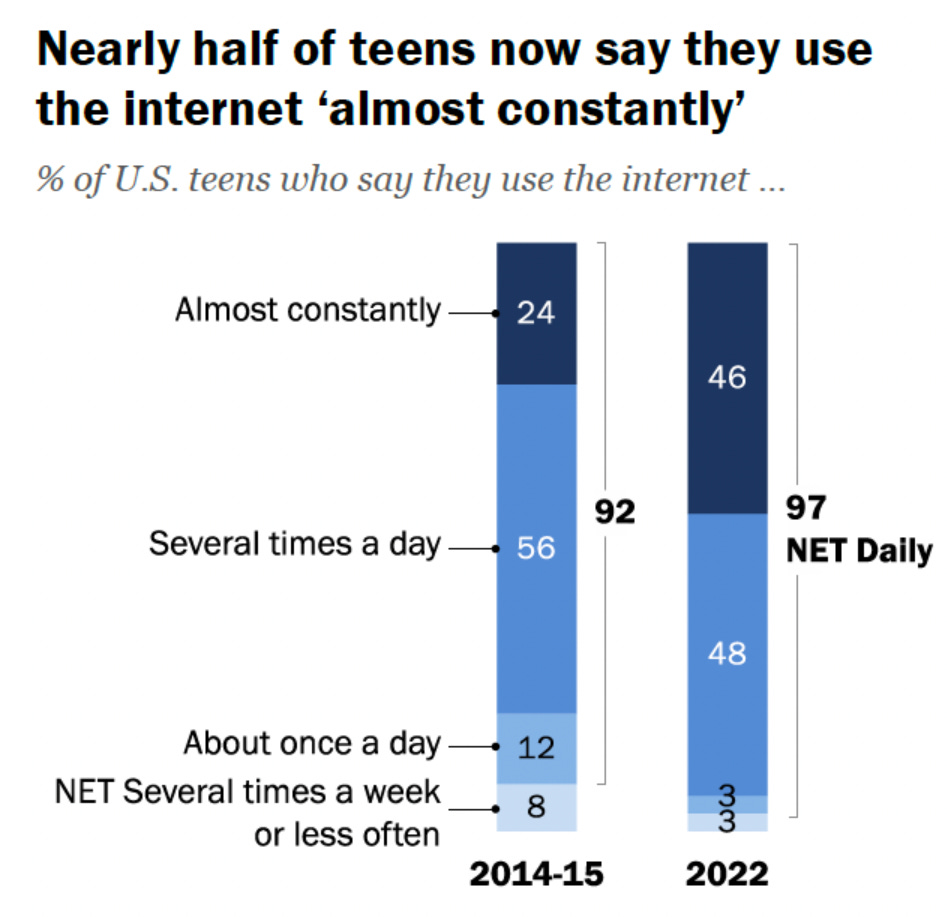

1. We are constantly connected to the Internet

This trend is pronounced for younger Americans, if not surprising, given that younger generations grow up not knowing the days before widespread adoption of the Internet.

This trend is likely only to increase: we will continue to spend more and more time online.3

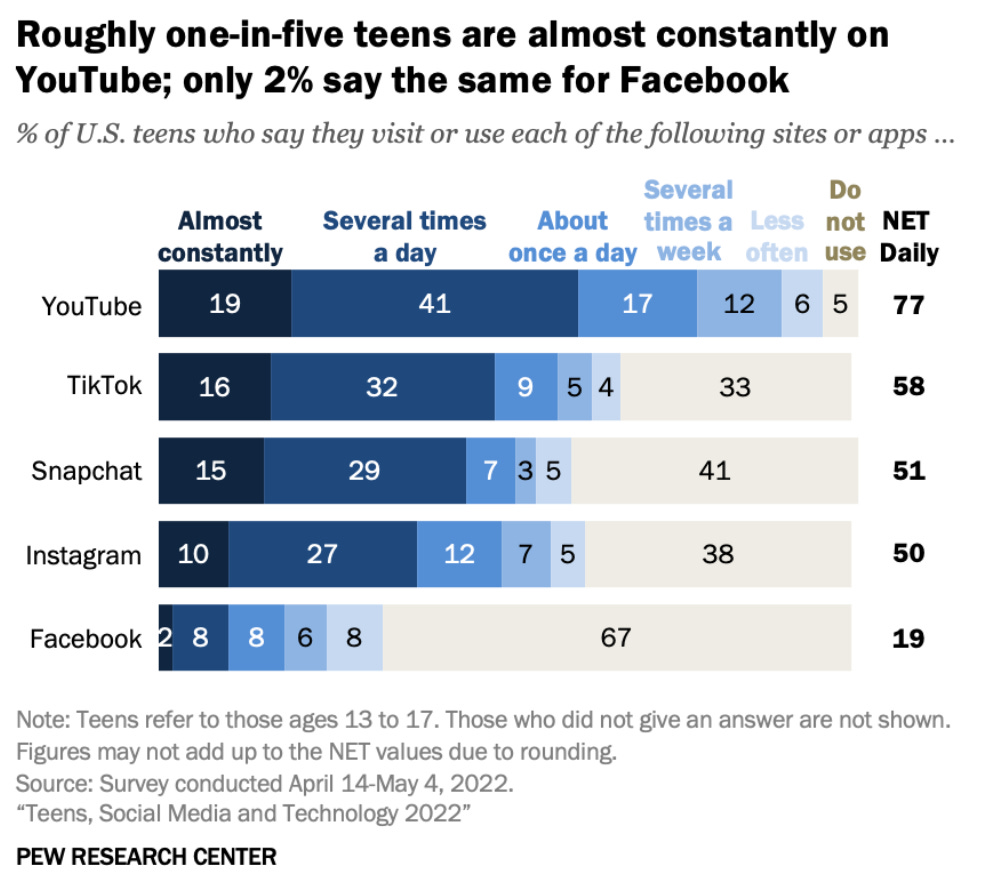

2. Social media sites and apps are a big part of Internet usage

Nearly 20% of teens spend over five hours a day on social media, according to a U.K. study. And the average nets out to three hours. Youtube and TikTok, two platforms focused on video content and virality, rise to the top.

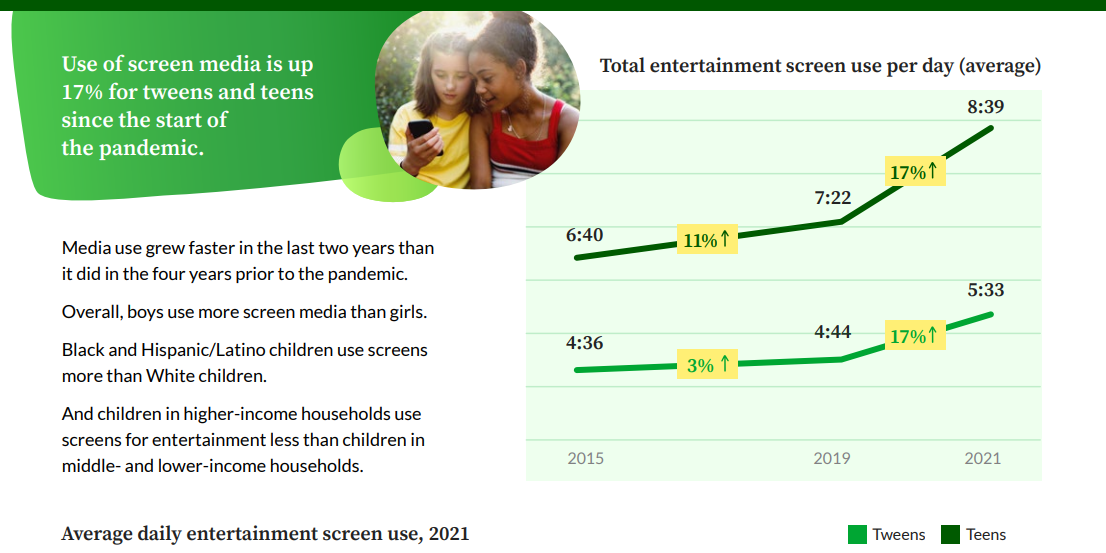

3. Entertainment drives a large portion of screen time

Much of the screen time is focused on entertainment. The pandemic accelerated this trend. Comparing the number of hours a day spent on the Internet, social media, and entertainment from different sources can muddle the message when looking at the exact number of hours.

The point is that usage is large, entertainment-focused, and growing.

4. Our attention spans are declining

Not surprisingly, the time we spend on any one task has declined over time:

“In 2004, we measured the average attention on a screen to be 2½ minutes,” Mark said. “Some years later, we found attention spans to be about 75 seconds. Now we find people can only pay attention to one screen for an average of 47 seconds.”

And once we distract ourselves/shift our attention, it is hard to get back on track with the original task, taking on average 25 minutes to settle back into working. Screens take up more time entertaining us and we shift our attention from tasks more frequently. And as a result, heavy use of social media can also negatively impact critical thinking skills.

The common comparison here is to a goldfish, though whether or not that is a fair comparison for either the fish or humans is hard to tell. Likely neither. Certainly the Internet didn’t create the propensity of humans to distract themselves. Nor does it only contain click-bait junk. But when human nature runs up against algorithms built to maximize engagement (aka keep looking at our content so that we can sell more ads), we trend towards distraction.

5. Advertising, advertising everywhere

The Internet is built on ads. The free social media apps are built on ads. If you aren’t paying for it, you are the product. Some websites become almost unreadable under a barrage of advertising.

And this isn’t too far off what was depicted in Idiocracy for viewers watching television. Ads surrounding entertaining content:

Unless the advent of generative AI dramatically upends the search and advertising business completely and changes how we see and consume content en masse without ads, this trend is likely to continue.

6. Cracks in Democracy

Idiocracy doesn’t specifically address autocratic backsliding, but it does portray the cult of personality around a populist demagogue president. The parallels between President Trump and President Dwayne Elizondo Mountain Dew Herbert Camacho from Idiocracy (yes, in the future, presidents will sell advertising rights to part of their names) exist on the entertainment value of the presidency.

Donald Trump’s populist rise isn’t the only example of populist demagoguery (Orban in Hungary and Bolsanaro in Brazil, etc). The V-Dem Institute, in its 2022 Democracy Report, highlights the democratic backsliding over the past decade: “The level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen in 2021 is down to 1989 levels. The last 30 years of democratic advances are now eradicated.” Seventy percent of the world is living in an autocracy, compared to 44% in 2011. This trend is concerning, especially if entertainment-focused demagogues continue to rise and drive the backsliding.

While Trump no longer holds executive office, the ongoing indictment proceedings plays into his sweetspot: earned media driving him back to relevance and boosting his presidential fundraising. He is still relevant.

7. The derision of expertise

Tom Nichol’s The Death of Expertise, published in 2017, outlines a trend anti-intellectualism and resistance to learning in the face of almost infinite knowledge through the Internet. And we saw this throughout the pandemic and most recently through the bank run on Silicon Valley Bank: no one trusts experts AND everyone thinks that they can/should be an expert on vaccines, banking systems, the topic of the day. This trend follows hand in hand with misinformation and disinformation. Everyone can find a source of information to support a narrative they want, which also means that narratives can be created to support any position and be pushed to manipulate others. Generative artificial intelligence will likely only exacerbate this problem in the short run.

Wrapping it up: Citizen Thrill and Citizenville

Idiocracy and Citizenville portray two wildly different views for society. One was created as satire that has hit too close to home as it aged. So much so that the Urban Dictionary entry for Idiocracy states: “A movie that was originally a comedy, but became a documentary.” The other is an optimistic call to create better government through technology.

A big difference that has not explicitly been stated here is one of agency. Idiocracy depicts passivity - the incremental decline of humanity as we passively consume. We dull our thinking and our senses, aided by companies profiting by our desire for pleasure. This argument encompasses drug use as well, though it hasn’t been discussed in this post thus far.4

Citizenville’s vision only works through direct action. It charts (and calls for more) progress through direct engagement between government and its citizens using technology. This activity takes deliberate work and explicit engagement of citizens with their government. There needs to be active involvement by citizens. What makes Idiocracy’s critique powerful is that it shows the path of least resistance from an individual level. The identity of “citizen thrill” is much easier to embody on a moment to moment basis, given the design of technology and apps we use. Even without trying, we fall into this pattern.

This point on agency is just as important the next narrative, Citizen Disassemble, as well. Stay tuned.5

But what isn’t when it comes to technology in California?

Some speculate that the corporate/consumerist critique hit too close to home for Fox to support a full release.

And if the metaverse comes to fruition, "online” may not be the right term anymore.

I recognize that the phrase “stay tuned” in a post about how we mindlessly consume content through a screen isn’t the best phrasing unless I was trying to be delibarately tongue-in-cheek. I couldn’t decide so decided for a footnote. Which may have the effect of killing the joke since once you have to explain something it loses its humor. But here we are.