““How did you go bankrupt?” “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” - Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

“The chains of habit are too light to be felt until they are too heavy to be broken.” - Warren Buffett1

****

The debt ceiling debate rears its head again. President Biden, Speaker McCarthy and their respective parties seek out a political solution in the coming week(s) to avoid the U.S. defaulting on its debt. Politicians and pundits point fingers in every direction. Economists, technocrats, and constitutional scholars argue for ways around or through this political dance. There seems to be some progress between the two sides, but who knows, we are still on the merry-go-round.

Yet, the vast majority of the debate misses the root cause of this political circus. And in doing so, the conversation avoids grappling with how to solve the problem instead of managing it.

Unfortunately this oversight is a feature of modern American political debate generally. The “win” of raising the debt ceiling, with or without changes to federal spending, won’t solve the underlying problem. We will be in this same position again next time the debt-ceiling comes up for a vote. Ineffective governing processes will persist, even though they don’t have to.

In 4 bullet points

The debate over the debt limit is a manufactured, short-term problem that persists due to the political opportunism it affords lawmakers.

Existing solutions to the problem focus on long-term fiscal responsibility, an important goal but not the underlying solution (or even the underlying problem).

The hobbling of state capacity and unnecessary legislative inefficiency, as exemplified by the debt ceiling fight, is the fundamental problem. The current actors in the system benefit from no change to the status quo.

There are no easy solutions here. But if this problem isn’t addressed seriously, much larger problems will emerge for democratic governance.

What is the Debt Ceiling and how did we get here?

Congress enacted the debt ceiling - a legal limit as to how much outstanding debt the U.S. government can carry - during WWI. The legislated ceiling set an aggregate limit, as opposed to approving individual bonds, to help speed up and streamline the financing of mobilization and war efforts. The debt ceiling is separate from the budget:

Raising the debt limit is not about new spending; it is about paying for previous choices policymakers legislated. Brookings

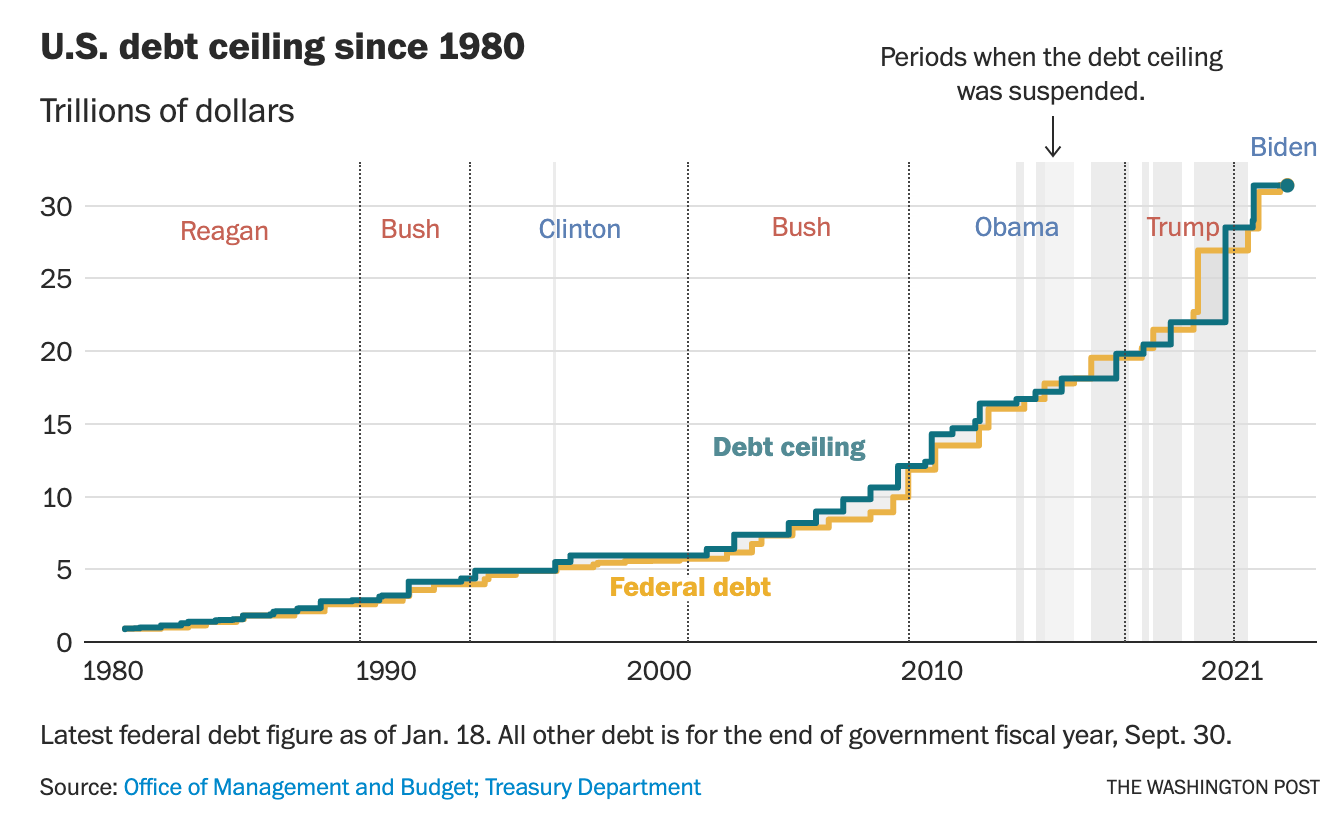

Since 2001, Congress has suspended or raised the debt ceiling 20 times. Going back to 1968, that number is 78 times. Congress has yet to fail to act to avoid defaulting on our debt.

There is a lot of noise around “this time is different.” And some of these concerns are valid as Speaker McCarthy looks to wrangle a caucus who demanded some serious concessions to give him the Speaker’s gavel at the start of this year, and President Biden looks to protect his legislative accomplishments from the Republican fiscal meat cleaver.

We’ve never not raised the debt ceiling. And given past brinksmanship and the myriad warnings of dire consequences if America does default on some of its debt obligations, it seems (feels?) likely that the trend of a brokered agreement will continue. But it only takes one deviation to fracture the trust underpinning our financial system and for this time to truly be different.

And the loss of that trust could lead to severe impacts: depression and increased unemployment, depreciation of the dollar and increasing prices, social security payments not being delivered, U.S. stock market crashing (with banks taking it especially hard), money market funds “breaking the buck,” and global markets declining.

The Current Debate: the short-sighted approach

Not surprisingly, the debate around the debt ceiling falls squarely in the realm of how we raise the debt limit. The simplifed positioning as Biden and McCarthy have agreed to talk is as follows:

President Biden is advocating for a “clean” raising of the debt limit. It is just a mechanical necessity to provide funding to spending that Congress already approved.

Republicans, led by Speaker McCarthy say that in order to raise the debt limit, there should be spending cuts. And not surprising, the proposed cuts are aimed at Biden policy victories thus far, including EV tax credits and student debt cancellation.

Both Biden and McCarthy are focused on the short-term mechanics of the debt-ceiling to achieve long-term policy wins. Democrats don’t want to haggle money that was already appropriated by Congress. And Republicans want to use the deadline to push their budget priorities. Remember, never let a crisis go to waste. You can malign the Republicans for their hostage taking actions here, but parties in the minority have historically been vocal about the long-term fiscal health of the country when the other party is in power…only to turnaround and forget those concerns when they are in control.2

What is needed: Long-term thinking AND action

The obvious need here is serious thinking and action on the long-term fiscal health of the country. There are myriad proposals, solutions, and priorities when thinking about dealing with the federal debt.

I am not an economist and this post isn’t geared towards solving the fiscal health of the country. The simple view of this issue is that our current debt-to-GDP ratio is 124%. And it is projected to continue growing. As debt grows, this can hurt growth and require more resources to pay for that debt.

Thus, revenues need to go up and/or costs need to come down. There are some headwinds when thinking about how to address:

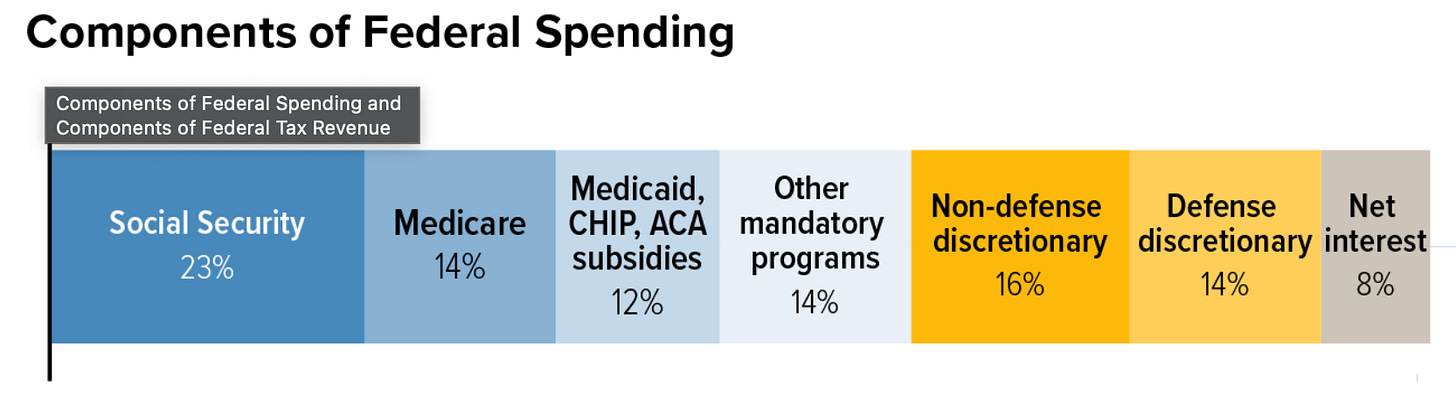

With rising interest rates, debt servicing costs go up

With an aging population, Social Security and healthcare costs are also going up

Mandatory spending, which includes entitlements and other spending not set by annual Congressional appropriations, makes up more than 60% of the federal budget. And there is always the spectre of more geopolitical conflict that could balloon defense spending.

Ultimately, there is no “magic” number for debt-to-GDP for the U.S. but it concerns many economists and we could run into a situation where our fiscal concerns could become an issue “gradually then suddenly,” to borrow a phrase from Hemingway.

This issue is known to policymakers. There is acknowledgement from folks around the table that it needs a solution. When and how that solution comes is a function of the second long-term shift needed.

Long-term process reform

What is not talked about seriously is rethinking the debt-ceiling as a political process and what it says about the effectiveness of American government. A lot of time and energy goes into thinking about how to solve federal spending, yet almost no time goes into thinking about how we fix the budgeting process, create more effective government, and align the incentives for lawmakers to create sustained, long-term decisions for the country.

Like all change management, addressing the habits and processes is much more important than just focusing on the outcome. If the incentives for political actors encourages more brinksmanship and last-minute wrangling, then that’s what politicians will gravitate towards. If there is a short-term win to be had through an inefficient process then that process will metastasize. Whether it’s needing to raise the debt-ceiling 20 times since 2021, the increasing penchant for Continuing Resolutions, or fights over the Filibuster, inefficient processes are the norm.

And it is more than just inefficiency. What is sacrificed here is effective government - the trust in government and the power of the state (broadly) to act and achieve goals on behalf of the American people. And we should want an effective government. Having a well-functioning state is a good thing!

Yet, so much of governance debate boils down to the size of government - should it be larger or smaller? Should it have more resources or fewer? It is easy for some to say government should take on more, regardless of how effective it is. On the other side, it is even easier to point at such a large institution and say “big government is bad.” But size isn’t the issue. Effectiveness is.

And that effectiveness applies not only to the federal agencies but also to Congress.

And this is the point: raising the debt ceiling should not be a fight in a well-functioning government. In an effective government. If our budgeting process worked, there wouldn’t be a dance to raise the debt limit to meet the funds already approved to be spent!

And yet, we have this fight because exploiting a broken process is easier than acknowledging that building state capacity should be a priority for the American people, and thus the government that represents them. It is far easier to continue to rely on bad habits to manage the federal government. And if this continues to be the trend, we may just awake one day only to realize that the chains of our ineffective habits have led the gradual and then sudden bankruptcy of our institutional capacity.

Attribution of this quotation to earlier thinkers is hard to validate but it is suggested online that Buffett is paraphrasing or quoting Bertrand Russell or Samual Johnson.

Fiscal conservatism used to be a stronger tenant of the Republican Party, but there is scant evidence that those talking points are anything more than talking points now.

Mint the coin?