This post is the second in a series focused on the emergence of the digital age and how this advance may not always equate to positive outcomes for government, technology and society.

Start with the first two posts:

Ctiizenville - outlines the positive argument for technology enabling government engagement with citizens and a more dynamic political life.

Citizen Thrill - covers the erosion of civic life and society through tech’s drive to always entertain.

This post looks at the digital age from another lens - one of technology eroding the institutional foundations of society. This argument is presented in The Revolt of the Public by Martin Gurri.1

Summary of The Revolt of the Public

Gurri, an ex-CIA analyst, penned The Revolt of the Public to analyze deep societal transformations brought about by the digital age. The book investigates the impact of the internet and social media on the traditional institutions of authority, such as governments, media organizations, and experts. This disruption created a new normal for the public sphere. A normal defined by skepticism and distrust of these traditional institutions.

Skepticism and distrust arises from the democratization of information. The Internet and social media empower individuals to express their opinions and share information globally in real time. This new power unleashed a surge of public discontent with traditional hierarchies, as people became disillusioned with perceived failures of the elite. Revolt comes from the public’s desire for greater transparency, accountability, and participation in the decision-making process.

A note here: the concept of “the public” does not refer to all people, or even one block or mass of people following a smaller group of leaders (like the 20th century mass movements). Instead, Gurri uses the term to refer to those individuals who are interested enough in an issue to get involved. Thus, the idea of “the public” actually shifts for different scenarios:

[The Public] is not a fixed body of individuals. It is composed of amateurs, and it has fractured into vital communities, each clustered around an “affair of interest” to the group.2

The argument thus can pull together many different events - the Occupy Wall Street movement and the Arab Spring are two of Gurri’s many examples. The public is a force for challenging traditional centers of power, and this can lead to swift change and destabilization of elite hierarchies that the public see as unfair and unjust.

In the case of the Arab Spring, the digital age forged the tools for the public to challenge the dictatorship of Hosni Mubarak as it put stress on the dictator’s rule. Gurri argues that this is emblematic of the new normal for institutions more broadly:

…the ruling class confronted what has come to be called “the dictator’s dilemma”—a frequent affliction of authority in the new environment. The dilemma works this way. For security reasons, dictators must control and restrict communications to a minimum. To make their rule legitimate, however, they need prosperity, which can only be attained by the open exchange of information. Choose.3

No longer can oppressive regimes keep a lid on all sources of information - it is much harder to censor the whole Internet - just look at how hard it is for China to maintain its Great Firewall. The emergence of the digital age can be an incredible force for good against oppressive regimes.

However, the increased availability and proliferation of information and data make it difficult to separate truth from fiction. Misinformation and conspiracy theories blossom and thrive in the digital age, further eroding trust in the traditional institutions of power. Reportedly, as of early 2022, approximately 16% of Americans believed Qanon conspiracy theories.

The democratization of information, the extreme growth in the volume of information, and the ease of spreading misinformation and disinformation all lead to various signs of the revolt of the public: populist movements, social protests, and the election of outsider political candidates.

In a phrase, The Revolt of the Public is about the digital age catalyzing societal entropy: The public challenges the status quo in society, rebelling against the existing institutions and fracturing the order that exists. Yet, the public does not wish to replace this authority and have “no intention of governing…[nor] no capacity for exercising power.”4 Disorder and chaos are the results of this new nihilism ushered in by the digital age.

Is Gurri right?

The power of Gurri’s argument comes from the myriad examples after he wrote the book. He writes the explanation for Trump before Trump takes power. The rise of right-wing populism around the world, the continued destabilization of democracy, and declining trust in media all add further bolster his analysis. And we see more mistrust, misinformation, and disinformation spreading.

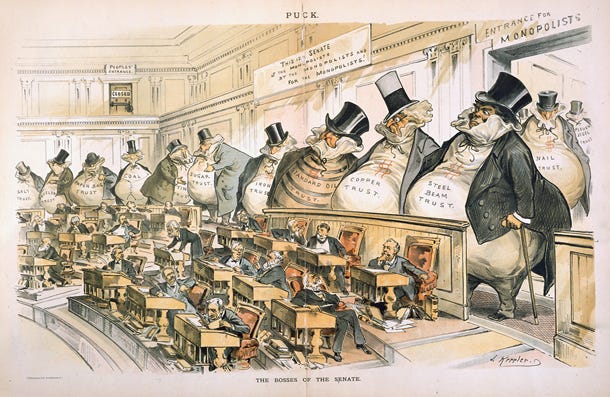

But can all of this be explained by the digital age? Hard to say. Populism and societal revolution is not new. Democratic revolution swept through the American colonies and jumped to France and Haiti. The turn of the 20th century saw populist movements challenge industrial interests.

So, the question arises: How much of recent waves of populism and backlash can be ascribed to a significant phase change brought by the digital age? Versus how much of recent years are just another example of episodic backlash by the masses to institutions of power?5

The answer is likely a mix of both. Unrest and pushback against established authority is not new throughout history yet the digital age created the means to challenge authority broadly in a manner that looks much more nihilistic than in the past. The power in Gurri’s argument is tying disparate events together and highlighting the entropic tendencies that the digital age encourages.

Citizen Disassemble versus Citizenville

It is quite easy to see the contrast between Gurri’s thesis of nihilism versus the hopefulness in Citizenville. The latter lauds the power of the digital age to create greater connectivity and cooperation between government and its citizens. Newsom’s idealistic vision is a civic-minded version of farmville, where citizens can interact digitally and build stronger communities in new ways by harnessing new technology. Gurri’s point is that instead of tending the crops in this digital farm, the public razed them to the ground. And then salted the earth.

Gurri’s argument is almost the direct antithesis to Newsom’s vision. Instead of utopian building of the digital world through government and civic engagement, mistrust and nihilism reign. Is it the complete picture? No. But it is a powerful lens with which to view and explain some of the more disturbing trends in the beginning part of the 21st century.

The full title of the book is The Revolt of The Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium. It was originally published in 2014 and updated in 2018 to include the election of Donald Trump.

The Revolt of The Public, page 29.

Ibid, Page 37.

Ibid, Page 70.