This post is part of a series focused on the emergence of the digital age and the argument that greater technological progress doesn’t necessarily equate to clear, positive outcomes for government, technology and society.

Read the proceeding posts: the positive case; Citizen Thrill; Citizen Disassemble.

The third negative lens with which to view the interaction of government and technology is one of mismatched speed. Namely, technological innovation is fast, deliberative government is not.

Which leads to the question: If the speed of technological innovation outpaces the government’s ability to effectively regulate this innovation, does it undermine the government’s credibility and ability to govern? The below lays out the case that the government may not be able to effectively regulate technology effectively at some point given the mismatch in speed by looking at the following in turn:

The pace of technological innovation:

The Internet enabled the creation of many different companies, business models, and new policy questions and implications for societies.

Technological progress continues to accelerate, in ways that we don’t fully appreciate.

The role of democratic government:

Democratic government is deliberative by design.

Elections incentivize short-term thinking.

Well-intended processes of an administrative state can have unintended consequences.

Technological progress

Understanding the rapid pace of technological change is hard to fully grasp. This struggle exists not only for the Internet Age but for all technological progress. For example an American adult who is 39 years old (median age in the U.S.) was born at a date closer to the end of World War II (with the development usage of two nuclear bombs) than to today. They were also born closer to the development of the first computer (ENIAC in 1946) than to the present day. And now researchers at Laurence Livermore Labs reached scientific energy breakeven and everyone has a computer in their pocket.

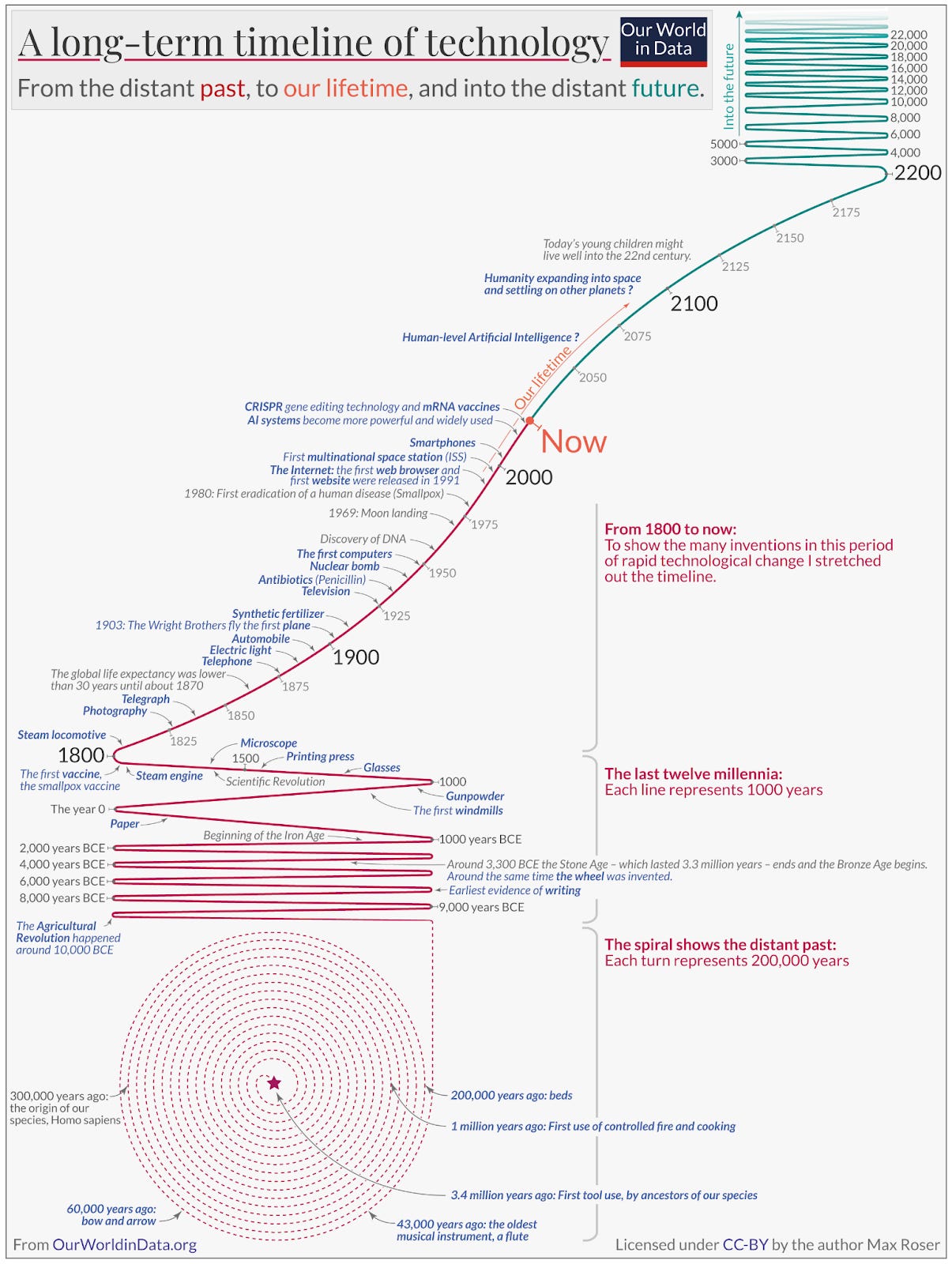

This pace is staggering. Almost every visualization of technological progress shows hockey stick growth - a period of slow development and then exponential growth. This continuous exponential growth has been dubbed “the law of accelerating returns,” and applies to a host of technological trends (Moore’s Law being the most well-known and oft-cited).1 Our World in Data has a trove of charts and articles on this rapid technological change that are worth exploring, and this one does a nice job of visualizing a lot of things in one image:

We take technological progress for granted. The invention of antibiotics occurred 95 years ago and we can now sequence the human genome for less than a $1,000 and use mRNA technology to design, develop, and ship a new vaccine in a matter of weeks.

Looking at the Internet and social media, 60% of the world is online after three decades:

And ~3 billion people use Facebook each month:

These trends are meteoric in pace and impact. Especially when looking at the amount of time that people spend on social media websites. These technologies take up a significant amount of time, and they didn’t exist two decades ago. It’s hard to grasp, especially for the portion of the population that comes of age alongside these technologies.

The quest for artificial general intelligence (AGI) stands to greatly accelerate this progress in ways we likely cannot comprehend, or even imagine (assuming we don’t use it to kill each other or aren’t killed by AGI due to misalignment).

This pace is exciting and tying it back to technological impacts on governing, Gavin Newsom captures the excitement of these changes in Citizenville and seeks to map out how social media could change democratic governance through applying technological change to existing institutions. But deliberative democracy and the existing institutions do not follow the same pace of innovation and are much harder to change.

The Pace of Democratic Government

In sweeping generalizations2, government is supposed to be stable, dependable, and reliable. Not having continuous exponential change in the way citizens organize and choose to govern themselves is a good thing.

The establishment of democratic government, in the U.S. and elsewhere, relies upon the social contract between citizens and their government, in effect giving up some freedoms for the protection of the government. It would not work well to have to renegotiate this contract continually! In practice there is no actual contract made between the governed and the government, but if a government slides into tyranny or abuses its power, citizens will revolt and look to establish a new government.

For the Founding Fathers, a key part of ensuring that the Federal Government didn’t abuse its power was to separate power into different branches of government. As James Madison wrote in Federalist Paper No 47:

The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.

Avoiding tyranny was a chief concern of the Founders, thus a structure designed to ensure “ambition must…counteract ambition.” This splitting of power was meant to impede the ability of any one individual (or group of individuals) from monopolizing power and infringing on the rights of American citizens. Additionally the creation of a bicameral legislature, with the Senate consisting of fewer members and longer term lengths, also helped to balance out the potentially more volatile House of Representatives.

Thirty-thousand foot civics aside, this stability in structure continues today and is a testament to the design of the Founders and the ability to have consistent institutions over time. There are many complaints about the inefficiencies of some of the processes and norms (filibuster, anyone?), legitimate fears about the attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, and ongoing threats to elections. Yet, overall American democracy has held up remarkably well and stayed fairly consistent over time.

That doesn’t mean there hasn’t been change to American government. There obvioulsy has - the two biggest of these changes are 1) the expansion of rights and the franchise and 2) the role the federal government has played in society. The expansion of rights is the most obvious way in which government operates now vs. the late 1700s. And after a Civil War, the Women’s suffrage movement, the Civil Rights era, we are still grappling with ensuring the rights of each American citizen.

The second piece - the role of government - isn’t as obvious to the casual observer. Yet, starting with the New Deal, the Federal Government took a much more active role in the lives of Americans (social security, federal deposit insurance to name a few that have been in the news recently).3

Yet, these changes have played out over a long time horizon. Even though the Civil War abolished slavery after four years of fighting, it took another hundred years and a mass movement to really push Civil Rights forward.

Political Short-termism

One of the benefits of technological development is the displacement of old, inefficient technology, processes, and companies. In capitalist societies this continuous process of improvement and progress disrupts old paradigms and drives growth. Government does not have this “creative destruction” built into the political process except via elections. The ballot box is a powerful tool to push for change, but it also creates distinct political incentives for politicians: get (re)elected.

And the push to get reelected can dictate policy outcomes, i.e. cutting taxes instead of taking a serious look at how to tackle rising entitlement payments with declining population growth. Much easier to give money back to voters than propose raising the retirement age, for example (just ask Macron). This dynamic favors the status quo. And using seemingly non-controversial or easy processes (e.g. debt ceiling) for political gain. And getting serious about long-term challenges is harder if taking an politically unpopular stance means you are no longer in office next election cycle.4

Administrative + Procedural hurdles

Another force counteracting rapid change is the way in which the administrative state acts. As Nicholas Bagley points out, the collective belief about procedural rules and their importance in creating accountability and guarding against abuses by the state can be misguided:

Procedural rules have a role to play in preserving legitimacy and discouraging capture, but they advance those goals more obliquely than is commonly assumed and can even exacerbate the problems they’re meant to solve.

It is easier to write more rules and create more processes in hopes of supporting certain policy objectives. It is much harder to peel these processes back, especially when having to work against the good intentions of creating the procedures in the first place. And this can mean we lose sight of the outcome.

What about regulation?

Regulation plays a key role in shaping markets and protecting consumers. Yet, as seen with recent technological developments (artificial intelligence, crypto-currencies, social media, ride-sharing apps, to name a few), technology is moving at a pace that makes it hard for the federal government to keep up. The obvious concern here is can the government effectively regulate technology, and can it do so in a timely, thoughtful, and meaningful manner?

If the hype we are hearing continues, there really are two things to consider:

Development of AI

Everything else

On artificial intelligence, it may seem buzz-y since generative AI models have taken the world by storm over the past ~6 months, but there are also a lot of concerns from AI researchers, philosophers, policymakers, and, well, a lot of people on how the development of artificial intelligence could bring about the end of humanity.5 It’s not worth going into the evidence here in detail, other than to note that some researchers penned a plea for a 6 month pause on all artificial intelligence research. Still others have more drastic suggestions: monitoring GPU usage globally and reserving the right to forcibly (maybe even militarily) intervene to stop the development of AI models. Regardless of the policy outcome, it is clear that there is a non-zero chance that rushing blindly into AI might mean the end of the world (for humans).

And, why is this different from other technologies? AI is different because we may have already missed the opportunity to effectively regulate it, given the global nature and fast pace of development. Eliezer Yudkowsky, one of the more vocal voices on AI ethics, lays this out on an EconTalk podcast:

…it seems to me that the game board has been played into a position where it is very likely that everyone just dies. If the human species woke up one day and decided it would rather live, it would not be easy at this point to bring the GPU [graphics processing unit] clusters and the GPU manufacturing processes under sufficient control that nobody built things that were too much smarter than GPT-4 or GPT-5 or whatever the level just barely short of lethal is. Which we should not--which we would not if we were taking this seriously--get as close to as we possibly could because we don't actually know exactly where the level is.

We may have reached and crossed the rubicon on AI. And there could be no effective way to stop the eventual development of artificial general intelligence that could threaten humanity’s survival. In that case, it really doesn’t matter how we think about regulation, other than the most drastic of measures.

Not only is this view quite pessimistic, it also doesn’t leave us with much room for action. If we are past the point of no return, who cares what we do? This nihilism isn’t constructive.

The second path still includes the non-nihilstic view of artificial intelligence, presuming we aren’t past the point of no return, and also encompasses other areas of technology. And whether it is privacy, artificial intelligence, cryptocurrencies, worker classification, etc. regulation lags behind technology. This problem is well known and isn’t new. Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act in 1887 to regulate railroads to counter unfair pricing and monopolistic behavior, trying to curb the excesses in a burgeoning industry.

Regulation is in effect backwards looking, with policies drafted and enacted based on current or past conditions. Laws aren’t written with “in the event we see X happen in the future, Y should happen.” And that’s a good thing! Spelling out all iterations of future technological development or all the things that could happen would be a poor way to govern. And this can lead to regulatory arbitrage - businesses profiting at the intersection or gray area of current regulation. Which then can require additional regulation or clarification.

But can this backward nature of regulation continue to keep up with the pace of technological progress? Can regulation remain relevant for companies and technological development in today’s world? The pessimistic answer is no, that governments will fall more and more out of step with society and technological development. Which will only fuel greater distrust in government, and transfer it to private companies.

How does this fit with Citizenville?

Tying this back to the rosy picture of collaborative government enabled by technology and the creation of a digital town square, the ability of government to engage with its citizens effectively through technological means requires it to keep pace with technological change.

Citizenville deals with social media and connectivity. The mutual beneficial flow of information, collaboration, and problem-solving. Yet, if social media create constant dialog but elections take place every two years (for example), there is a mismatch between real time feedback and results at the ballot box. Pushed to the extreme, one could argue that the recent usage of recall elections in California are examples of the impatience of social media ire butting up against the traditional political structure.

And on the other side, two years is a short amount of time, and the long-term issues facing communities and the nation more broadly require longer term solutions that may not be politically popular when remembered by voters heading to the ballot box next cycle. While technological development in a market economy drives innovation, it isn’t a given that government - the legislative, regulatory, or adminstrative processes - sees that same positive change. Companies can respond quicker to consumer demands. Government cannot match the same pace with citizens. Which, if pushed to the extreme, could result not in the collaboration of a technology-enabled government, but the full privatization of governing and service delivery. Indeed, if you look at science fiction, this could result in pizza delivery mafias enforcing law and order - a la Snow Crash. Anyway you slice it, not quite the continuation of a “a more perfect union.”

Tegmark, Max. Life 3.0: Being Human in the age of Artificial Intelligence. Page 68.

Cannot emphasize enough how sweeping and dilettante-ish this section reads if someone is a serious academic or student of political philosophy.

Again, this is a broad overview. There is much more nuance than pre + post New Deal.

Again, see footnote 2.

On the flipside, it could save humanity.